At North Howard Street, a painting of Lamar Jackson hovers above bold graffiti letterings, the bright purple and gold No. 8 in his jersey standing out to the white of his uniform. The Ravens quarterback has his hand up, displaying a peace sign.

To his left, there is a classic red stop sign — only this one reads “Stop Gun Violence.”

The mural is the newest addition to Graffiti Alley in the Charles North area, known as a sort of haven for street artists. It is also part of a larger public art effort by Kyle Holbrook, an artist and founder of the Moving the Lives of Kids Community Mural Project, to bring attention to gun violence.

“Public art is a powerful tool, and always has been, for activism,” he said. “In the community, people see it every day. It’s not like TV or radio or something where you can turn it off. It’s gonna be there every day as a constant reminder.”

Gun violence spiked in 2020, with over 19,000 people killed in shootings nationwide, according to Gun Violence Archive, a Washington D.C.-based nonprofit that tracks shootings. That was a 26.67% increase from 2019, which saw over 15,000 killings.

This year, Baltimore has seen over 200 homicides so far, and at least 380 nonfatal shootings, according to Baltimore Police. There has also been a rise in youth victims, with at least 25 people under the age of 18 shot this past year. The majority of gun deaths are from Black and brown communities.

Originally from Pittsburgh, Holbrook lost his first friend to gun violence at the age of 14, someone he used to play basketball with, he said.

Then, he lost another one in his later teens.

Then again in his 20s, and then his 30s.

By his early 40s, Holbrook said he had lost dozens of friends to gun violence and has been a victim of police brutality.

Holbrook keeps his artwork simple, in contemporary street art style with usually one or two colors, using brushes and acrylic paint.The signature peace sign can also be found in murals abroad, from Melbourne to Thailand.

This past year, Holbrook also painted murals to remind those passing by to wear a mask. In the French Quarter neighborhood of New Orleans, a pink and white Zion Williamson holds a basketball, half of his face covered by a teal mask. In the Arts District of Los Angeles, a mural displays veterans, one of them in a wheelchair, also wearing masks against COVID-19. Tiger Woods, in purple and lilac, holds a golf club as if he had just hit a ball in River North Art District in Denver.

But the “Stop Gun Violence” project began in Chicago before the pandemic took hold of the U.S.. He then went on a road trip to Milwaukee, Des Moines, Indianapolis and Columbus before reaching Baltimore this past weekend. His next stop is New Jersey.

“I’ve been seeing in every city I’ve been going, there’s just been a shooting,” Holbrook said. “Or there seems to be more guns in the streets.”

For Baltimore, the muralist said he wanted to add an extra element to his art.

Holbrook decided to paint Jackson, the former NFL MVP, for the “die-hard” fans, hoping that those who look up to the team will take on the message. The painting itself took about two hours Sunday morning.

It puts the issue at the forefront of people’s thoughts, he said. And the more people think about gun violence, the more people will think about solutions, he added.

“When things are happening in the Black and brown community, the laws and changes happen much slower,” he said. “ But public arts makes it so … everyone understands that this is something that needs to be done and is important to the community.”

But there’s also a therapeutic aspect to the mural, Holbrook said. He recently started talking about the people he lost to gun violence, he said, and painting his artworks have been a form of healing himself.

“And hopefully it’s some kind of healing for these communities,” he said. “To know that people haven’t forgotten.”

Marcus Harvey, the board president of the MLK Mural Project, thinks Holbrook was meant to do all of this. Harvey, who is a reverend, described Holbrook’s work as a calling.

He remembers one night when Holbrook got together for a mural project with people from Wilkinsburg, Pennsylvania, a community scarred by gang and gun violence. It was around 3 a.m., Harvey said, so dark that they pulled vehicles near the walls so that they could paint by the glow of their headlights.

“I never knew a paint brush could stop a gun,” he said.

Urban Collaborative Newsletter May 29, 2022

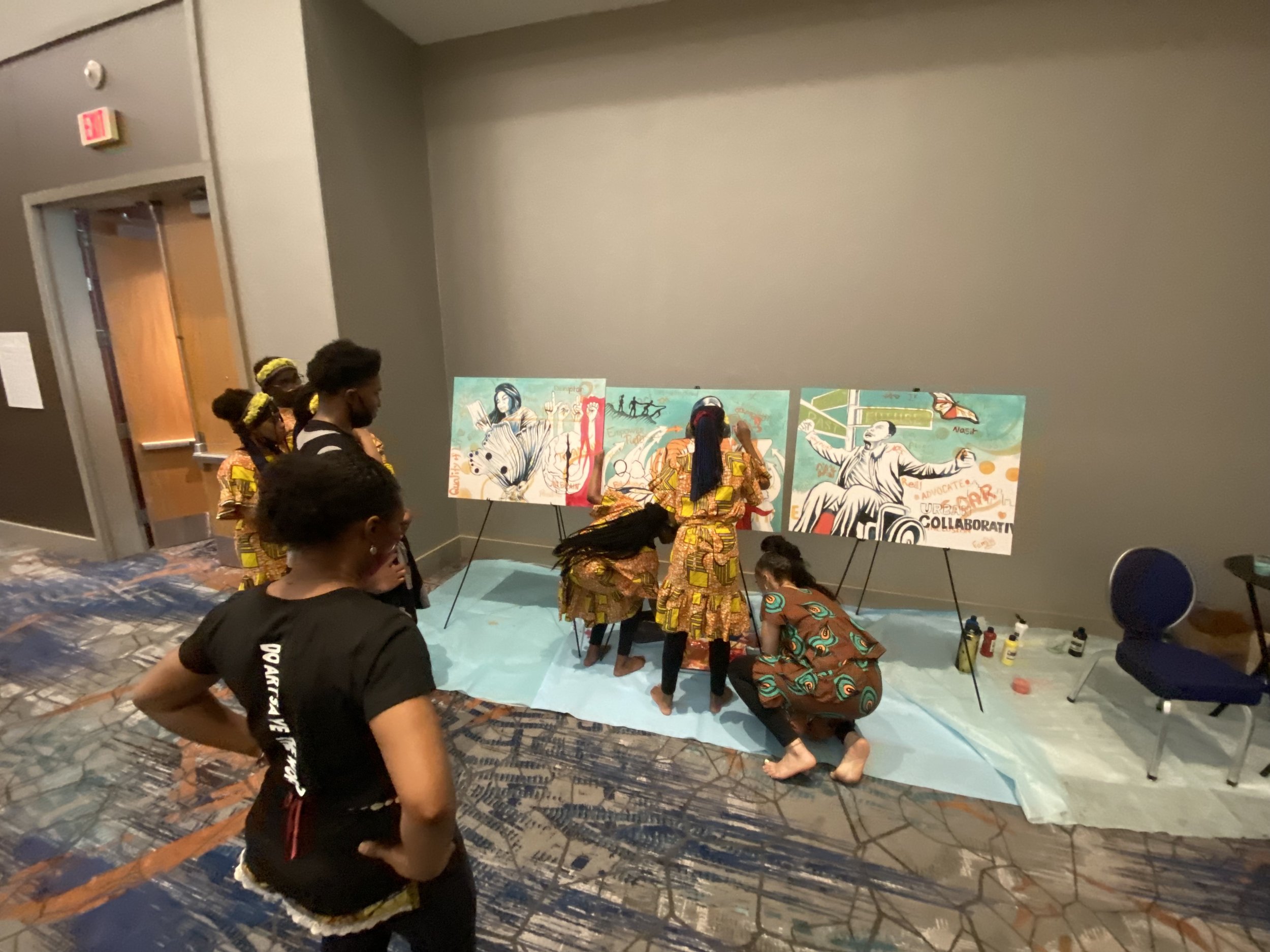

HILTON BALTIMORE INNER HARBOR- Urban Collaborative Conference May 22-29, 2022

‘Stop Gun Violence’: A New Baltimore mural calls attention to shootings

Baltimore Sun

•International Executive Artist Kyle Holbrook

Aug 10, 2021 at 11:37 am

GERONIMO LEWIS FOUNDATION LOGO- Imara Lewis and Jermaine Lewis commissioned a logo by Artist Kyle Holbrook in 1998 as part of The Baltimore Raven’s Foundation Network.